One of the most important lessons in investing is the distinction between price and value.

After examining a business’s management, financials and products, the next step is to determine the price you’re willing to pay for your share in that business (independent of market price), compared to the value you think that you’ll acquire.

The determination of value is a subjective exercise. Here are some considerations when choosing the price at which you are willing to buy a stock.

Margin of safety

The difference between price and value creates what Benjamin Graham called a margin of safety. This means investors shouldn’t buy a stock unless they believe the price they’re paying is substantially below the value they’re receiving.

The larger the discount between price and value, the larger the margin of safety and ability to protect the capital invested. In other words, an already undervalued stock is inherently less risky than one that is severely overvalued. The margin of safety acts as a safety net, should the investment thesis not turn out exactly as planned or if the markets take a tumble.

The margin of safety also provides advisors with the opportunity for heightened performance. If you can correctly identify a company that produces above-average economic returns, you can expect the value of its stock to increase over the long term. Also, you can expect an extra bonus when the market corrects the price of the business and closes the gap between price and value.

As is the case with the determination of value, the optimal margin of safety is a matter of taste. Some investors will be happy to purchase at a price equivalent to a 30% discount, while others may require at least 50%.

The industry, company characteristics and future outlook can all determine how much margin of safety is acceptable. A company with strong fundamentals and stable earnings, but that may see potential stagnation in the future, could warrant a wide margin. On the other hand, a fast-growing company you’re very confident in may only require a narrow margin.

At the same time, there’s no rule because a company with fast earnings growth may be deemed inherently more risky and thus require a larger safety margin versus the accomplished blue chip.

Valuation determines returns

The benefits of buying stocks when they’re undervalued occur even when using a simplistic approach to valuation, such as purchasing stocks with low price-to-earnings, low price-to-book values, as well as low price-to-cash-flow ratios.

These valuation methods have been effective in isolating stocks that are potentially undervalued, and that may be top performers over the long term.

Let’s look at the work of Professor Kenneth French of Dartmouth College as an example. He sorts U.S. stocks by their price in relation to book value, splitting them into five equal quintiles. Following each group’s yearly performance from 1952 to year-end 2011, the stocks in the bottom quintile outperformed those in the top, producing average annual returns of 19% a year. This compares to the lagging returns of 7.3% for those with the highest price-to-book-value ratios.

French also demonstrates that similarly good results can be obtained by investing in stocks when they’re trading at low price-to-earnings and low price-to-cash-flow multiples.

Patience provides returns

Occasional large declines are features of the markets. Take the crash of 2008 as an example. French’s performance data of stocks in the bottom quintile fell nearly 66% in the midst of the financial crisis. The good news is those losses were eventually reversed and surpassed the highs seen in mid-2007.

The lesson? Be confident and invest for the long term.

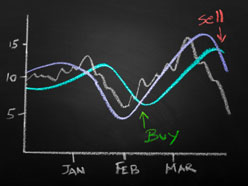

Market slumps aside, there is also plenty of action for individual stocks, whose share prices can move up and down. Whether these price swings are caused by short-term immaterial events, such as a missed quarterly earnings estimate or investor-shunned acquisitions, these events can create optimal opportunities to buy shares at a deep discount.

A question of quality

Sometimes low valuations are justified by weakening company fundamentals, lowered industry growth, or the loss of a key company executive.

The investor’s ability to decipher an undervalued but promising business from a cheap yet faltering one is what distinguishes investing success from failure. This is where experience, industry knowledge, and understanding the business and its management’s thoughts and processes come in handy.